Why Claims About “Protesters Attacking Mosques” in Iran Are Misleading

In recent days, Iranian state media and officials have shared selected images from protests across the country. These images are used to claim that protesters are attacking mosques and setting them on fire.

The goal appears clear. The authorities want to provoke religious emotions and mobilize their religious base. They also want to influence public opinion, especially among Muslims outside Iran, for whom mosques are respected and sacred places.

But this narrative is misleading. Showing isolated images without explaining the role mosques play in Iran gives an incomplete and distorted picture.

1. Only selected images and claims are shared

It is not clear how many mosques were attacked, or in which cities. Iran has no free or independent media access, and the internet has been heavily restricted. Because of this, it is not possible to independently verify government claims or confirm the images that are being circulated.

What we can say with confidence is that the information released so far is limited and selective.

As an example, we closely reviewed reports published by the Telegram channel of Iran’s state broadcaster between January 9 and January 13, 2026. This channel has been one of the most active sources publishing videos and news against protesters since the near-total internet shutdown.

Between January 9 and January 13, the channel referred to attacks on 33 mosques. Most of these claims were vague. For example, it said protesters attacked “26 mosques in Gilan province” or “one mosque in Sabzevar” or “two mosques in Farahabad and Marvdasht.” In only four cases were specific mosques named:

On social media, one more mosque in Tehran was mentioned: Nabovat Mosque, also known as Al-Nabi Mosque, in Haft-Hoz Square, Narmak.

Based on these reports, around 35 mosques were said to have been targeted. Iran reportedly has around 85,000 mosques nationwide. The number being discussed is very small in comparison.

The images and videos themselves are also limited. It is often unclear what exactly was damaged. Was it the mosque building itself, an outer wall, or nearby structures? Who caused the damage? Without independent field access, these questions cannot be answered with certainty.

What we are seeing so far is a one-sided narrative from a government with a long history of spreading incomplete or misleading information during times of unrest. Factnameh has previously documented similar disinformation campaigns by Iranian authorities during protests and conflicts.

2. Mosques in Iran are not only religious spaces

This context is missing from state media coverage.

In Iran, many mosques are not just places of worship. They are officially used as bases for the Basij, a paramilitary force under the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. The Basij plays a central role in suppressing protests.

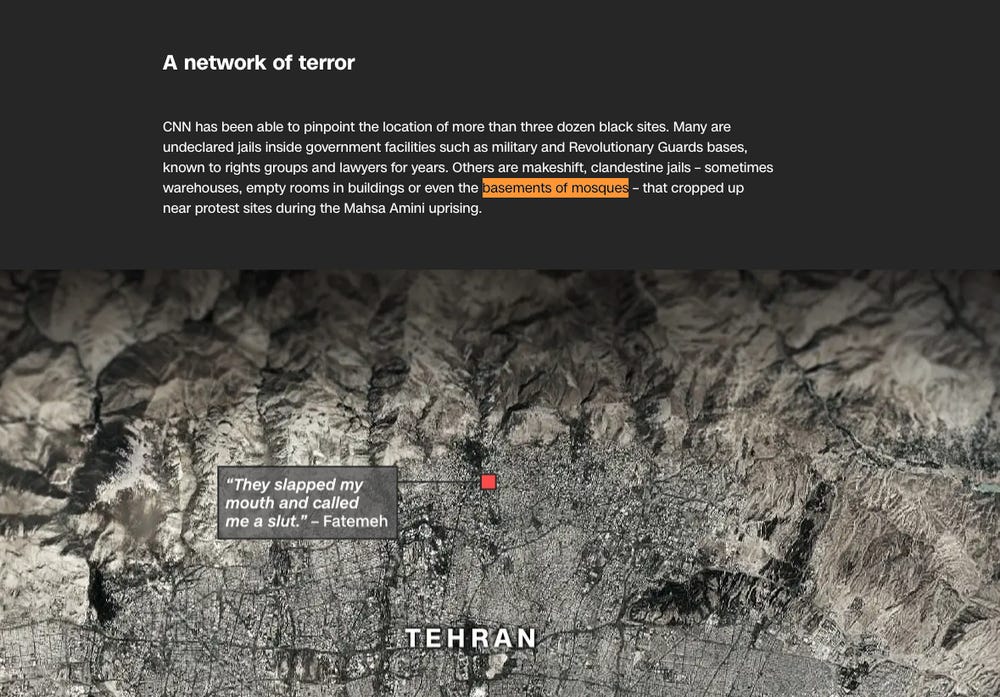

During the 2022 protests, CNN published an investigative report showing that some mosques were used as secret detention centers. Detainees were held and tortured there. According to this report, Basij units operating from mosques were directly involved.

Screenshot from a CNN investigative report on Iran, highlighting the use of mosques as sites for detention and protest suppression.

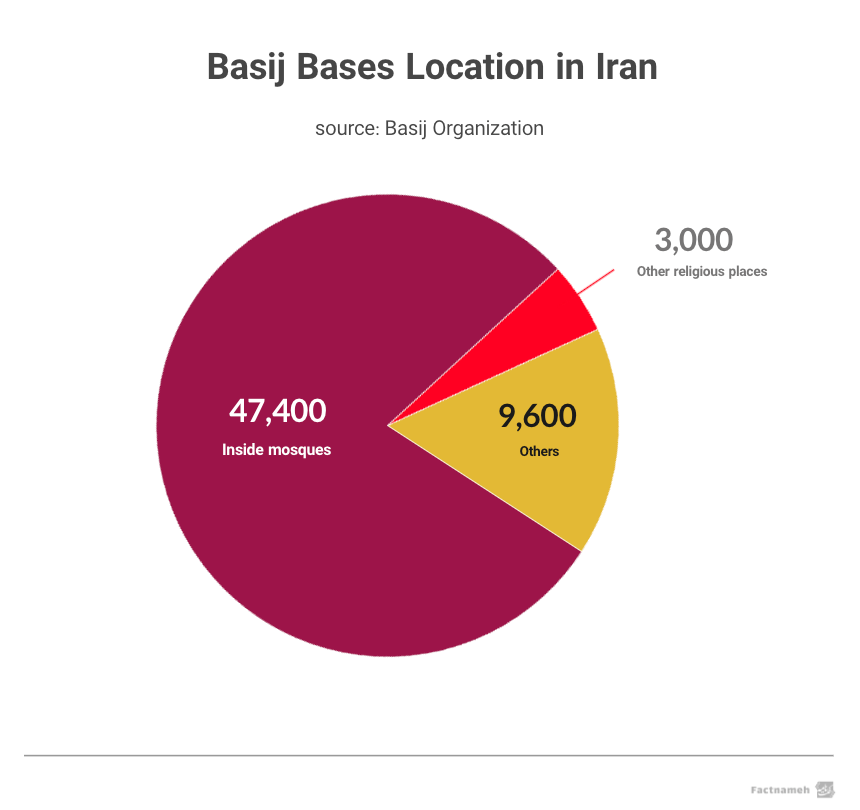

Based on official Basij statistics reviewed by Factnameh, nearly 50,000 Basij bases are located inside mosques across Iran.

In August 2024, the head of the Basij Organization for Mosques and Neighbourhoods stated that 79 percent of Basij resistance bases operate from mosques, with another 5 percent located in other religious sites. Two years earlier, the same official said there were about 60,000 active Basij bases nationwide. Taken together, these numbers suggest that more than 47,000 Basij bases operate from mosques.

During the current protests, despite communication blackouts, there is strong evidence that mosques were again used to organize repression. On the night of January 9, a senior IRGC official appeared on state television and called on Basij and pro-government forces to gather in mosques and bases.

When security forces operate from mosques and use them to organize violent crackdowns, it is not surprising that clashes may occur around these locations.

3. What we know about specific cases

Al-Rasul Mosque, Kaj Square, Tehran

Images from January 9 showed flames near Kaj Square, with Al-Rasul Mosque visible in the background. A closer look shows that the mosque itself was not on fire. Early reports focused on a burned police motorcycle and a police booth nearby, not the mosque building.

So far, no images have shown fire damage inside the mosque. Even state media footage published the next day only shows the exterior area.

This mosque hosts an active Basij base. A report by Tasnim News Agency, which is linked to the IRGC, explicitly referred to the burning of a Basij base at Kaj Square, which appears to be the same site.

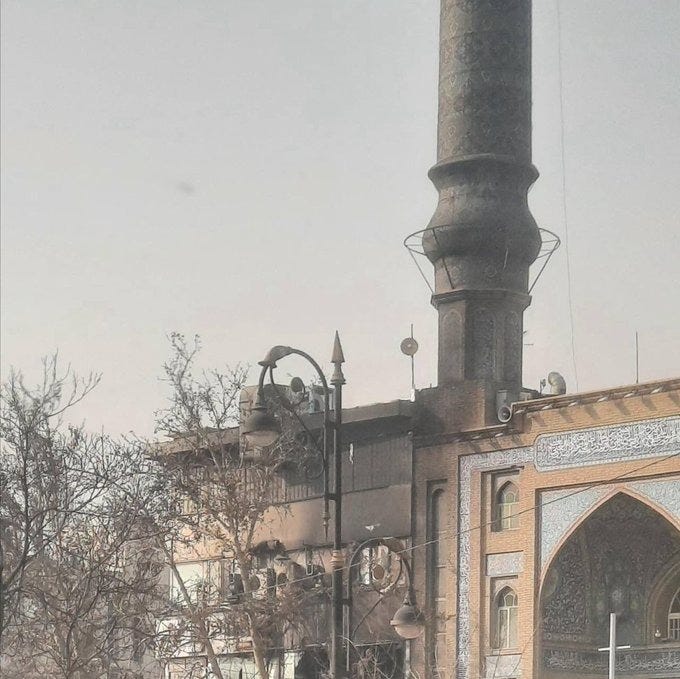

Nabovat Mosque, Narmak, Tehran

On January 11, images circulated showing damage to a minaret at Nabovat Mosque.

Archived religious media sources show that the “Martyr Ghaffari” Basij base operates from this mosque. Online traces of this base’s activities are still visible.

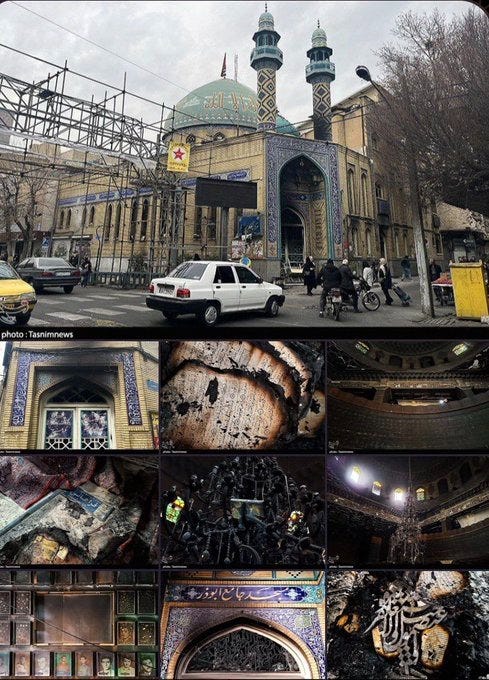

Abuzar Mosque, Fallah neighbourhood, Tehran

On January 11, images showed fire damage at Abuzar Mosque in southwest Tehran. State media described this as “terrorists burning a mosque.”

However, many social media users identified the mosque as a key gathering point for Basij forces involved in suppressing protests.

This mosque hosts an active Basij base that openly recruited members on social media until weeks before the protests began.

Mahdavieh Mosque, Karaj

State media also reported an attack on the Mahdavieh Mosque in Karaj. This mosque hosts the “Shahid Sobhani” Basij base, which has recently participated in military training activities, so-called “security drills”.

Ignoring the full context of how mosques are used in Iran turns a complex reality into a misleading narrative. By omitting the role of Basij forces and the organization of repression from these sites, state media and officials are framing protesters as attackers of sacred spaces. This selective portrayal is designed to provoke religious emotions and discredit protesters, both inside Iran and abroad.

This contextual breakdown is incredibly valuabel. The frame collapses completely once you point out that nearly 50,000 Basij bases operate from mosques, which means these aren't purely religious spaces but hybrid security infrastructure. It reminds me of how urban warfare analysis gets muddied when combatants embed in civilian or cultural sites, except here the governmentitself established that dual use systematically. The 35 mosques out of 85,000 statistic also undermines the "widespread attack" narrative pretty effectively when the numbers are laid bare.